The Science Project That Resulted in ‘Die Hard’s Most Killer Stunt

Published on Aug 13, 2018

It’s the three-decades-old shot that everyone remembers: up-close on the villainous Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman) as he falls to his death from the Nakatomi building at the hands of John McClane (Bruce Willis) in John McTiernan’s 1988 action thriller Die Hard. The shock on Rickman’s face — reportedly the result of being released slightly early as part of the fall — is one of the stand-out stunts from 1980s action films.

It’s also a shot that took advantage of what was then cutting edge optical — not CGI — special effects technology and some ingenious mathematics to bring the stunt to life. Here’s how the special effects wizards back then from Boss Film Studios made it happen.

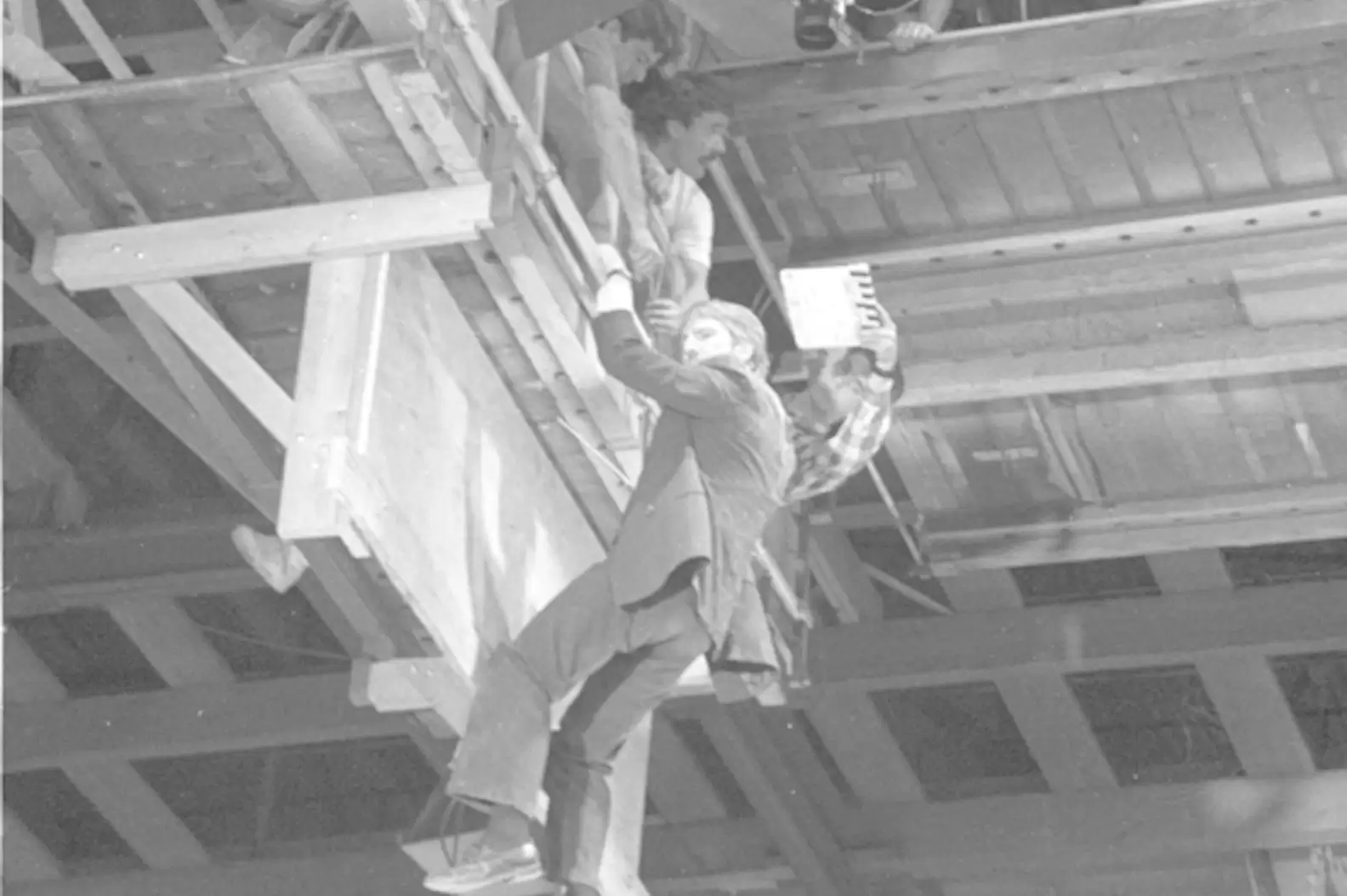

In order to get the shot, and make sure audiences saw the grief on Gruber’s face, Rickman had to fall backwards onto what was essentially a giant blue pillow about 20 feet below (the blue color would allow the special effects studio to isolate Rickman from the shot and place him against a different background of the Nakatomi building).

“John McTiernan had to talk Alan into doing that shot because even stuntmen will generally not fall backwards — they like to see where they’re going,” says visual effects supervisor Richard Edlund, a veteran of the original Star Wars trilogy and who was nominated for a VFX Oscar for Die Hard, along with Al Di Sarro, Brent Boates, and Thaine Morris.

“When Alan falls away from the lens,” adds Edlund, “that’s true terror you see in his face. He’s really scared of falling backwards, as anybody would be, even though it was going to be a nice soft blue pillow filled with air below.”

To capture the moment with fidelity, the team at Boss Film Studios needed to film Rickman at a very high speed rate. The stunt was therefore shot at 270 frames per second, which resulted in footage that appeared more than 10 times slower than normal. The bigger challenge, though, was that the shot begins very close-up on Rickman all the way until he would have just hit the blue pillow — it was a fall that needed to be in focus the whole time.

So, how did the camera operator manage to do it? Boss Film Studios orchestrated a motorized electronic encoder system for the camera lens that was able detect the change in focus.

“The operator was looking through a ‘pistol scope,’ which had a little red laser dot in the center of the eyepiece,” explains Edlund. “He was following Rickman’s face as the actor fell away from camera. At the same time, the encoder was sending data back to a computer, which then crunched the information instantaneously and sent it back to the motor on the focus ring on the lens.”

“Basically,” continues Edlund, “we set the camera up and moved the lens to Position One and would record that point, then moved it a few more inches and did a logarithmic curve of test spots. Then the electronics guys could spline that and turn that into a smooth follow-focus program that would hold the focus on Alan automatically. So it was like a little science, and it required pretty astute engineers — mechanical and electronic engineers — to figure out how to do this.”

Edlund went into the shoot with Rickman planning to capture everything in a single take. He didn’t expect the actor to want to repeat the backwards falling stunt more than once. They got the shot, but Edlund says McTiernan talked Rickman into filming another, just in case. (Ultimately, the first take is the one that appeared the movie.)

The next step was to take that footage — a slow motion Alan Rickman falling backwards onto a blue bag — and composite it into a separate shot of the view falling down the Nakatomi building. This separate shot, known as a background plate, was filmed from the Fox Plaza tower, which stood in for the Nakatomi building in the film. Remember, this was before any CGI, so that composite took place on an optical printer, a device that allowed two pieces of film to be composited together.

Other things were also composited into the final shot, including stock certificates that had been let loose out of the window. “For those,” reveals Edlund, “we basically shot confetti, little postage stamp-sized pieces of paper that flitted around.”

The final part of Gruber’s fall is a separate shot of the character seen falling down the entire length of the building. This was achieved with a stuntman dressed like Rickman, falling with a special decelerator wire rig that cannot be seen on camera.

For all the work that went into the logistics of getting this iconic shot, Edlund is proud of the effects work that went into this Die Hard stunt and the fact that it has endured for 30 years. He also says that if he was tasked with achieving the same shot today, he would probably approach filming the scene in exactly the same way.

“The advantage that we had at the time was that it was in the analog effects era, and we had a machine shop with really high quality machine tools,” Edlund says. “We had a numerically controlled computer milling machine that let us make precision movement parts for camera movement. Effects studios don’t really have that kind of thing today.”