Sexism Onstage, With a Twist

By Claudia La Rocco Dec. 23, 2011

Female playwrights historically have not found Broadway a welcome home to their new plays, but this season has been a surprising exception. Along with a darkly comic one-act from the veteran Elaine May, Katori Hall and Lydia R. Diamond are making their Broadway debuts, and Theresa Rebeck, a Pulitzer Prize finalist, has her second Broadway production to date, the comedy “Seminar,” now at the Golden Theater.

Is progress necessarily progressive? “Seminar,” a play about the art of writing and the drive for success, tackles gender politics head-on; based on Ms. Rebeck’s pointed remarks about sexism on Broadway in a 2008 essay, you might think “Seminar” would come laced with a feminist agenda.

“Boys, boys, boys!,” the essay’s sarcastic opening lines read. “This year on Broadway it is a celebration of boys! Step aside, girls — it’s time for the boys!”

In her play, Kate, a smart aspiring novelist, echoes those lines with her final, cutting words: “Boys boys boys you just never get enough of yourselves, do you?”

Yet “Seminar” has its own insidious glass ceiling.

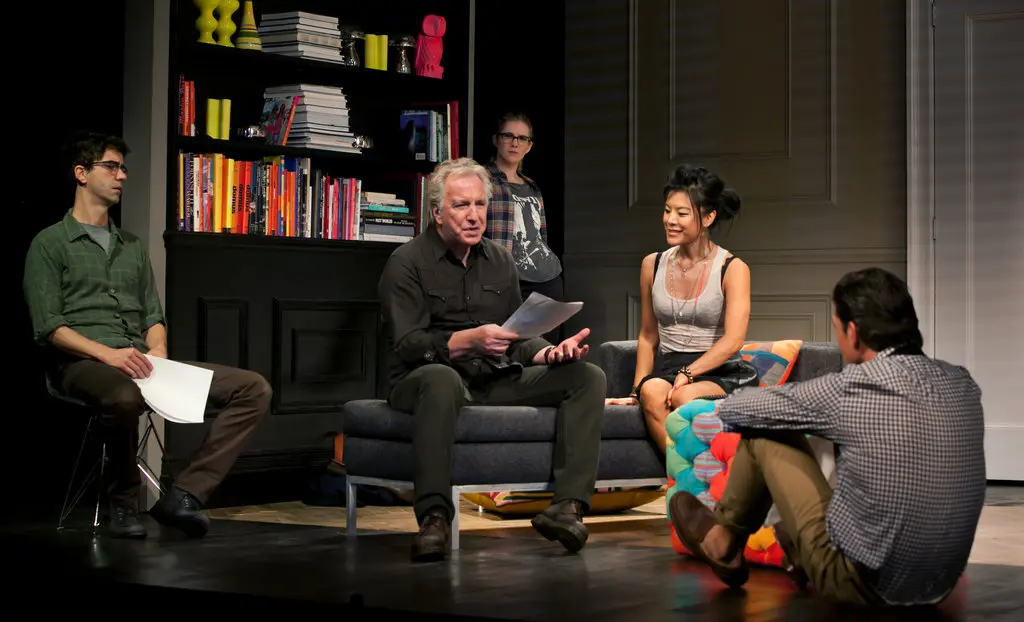

The plot revolves around a private course taught by Leonard, a hoary old lion of an author (Alan Rickman) to four ambitious young writers: Kate (played by Lily Rabe), another woman and two men. While Kate’s jibe at the “boys” comes during her final scene on stage, she does not get the last word of the play, which culminates (spoiler alert) in a celebration of the writer-as-tortured-artist, with the writers in question being two men: Leonard, who has by this point slept with both female students; and Martin (Hamish Linklater) who has slept with one of them, Izzy (Hettienne Park), an alarming Asian-sexpot caricature who bares her breasts early on, and seems well on his way to landing Kate as well.

The message seems to be: the women are around for sex, but intellectual love affairs occur between the serious artists. In the world of “Seminar,” they are men.

Ms. Rebeck’s literary name-dropping makes the point even plainer. Mentions of famous male writers abound: Frank Conroy, Tobias Wolff, Robert Penn Warren, Salman Rushdie and Jack Kerouac. When female authors get nods, they are troubling ones: Emily Dickinson, whose name Leonard invokes to taunt Martin, and Jane Austen, to whom Kate alludes at the beginning of a short story. Leonard rips this story to shreds without even taking it in, describing the narrator as “an overeducated completely inexperienced sexually inadequate girl.”

To call someone a girl is not a nice thing in “Seminar,” where the gendered insults fly fast and furious. There’s slang for female genitalia, and “whore” comes into play when Leonard explains what’s wrong with a story by the fourth student, Douglas (Jerry O’Connell). “Feminist” is another term of disdain — unless, as Leonard points out to Martin about Kate, “you catch one, when she’s right about to pop, it’s like, I couldn’t get her to stop.”

In other plays, Ms. Rebeck has exposed cultural hypocrisies among the so-called enlightened, and true to her modus operandi, “Seminar” trades in stereotypes. At least there is a Kate to argue with Leonard — in sharp contrast to another current Broadway production, Woody Allen’s “Honeymoon Motel,” one of three frivolous one-acts in “Relatively Speaking,” which, like “Seminar,” celebrates the true (male) writer-artist and rewards him with a much-younger blonde. Ms. May’s “George is Dead” presents even drearier depictions of women, but the playlets as a whole are such offensive throwbacks, it seems petty to quibble with how any one group is treated.

Ms. Diamond’s “Stick Fly,” which looks at an upper-middle-class black family and its secrets, offers a layered (if boilerplate) welter of class and racial politics. By the end, the play’s philandering, condescending family patriarch is somewhat cut down to size. As “Seminar” veers from satire to romance, by contrast, Leonard never gets his comeuppance. Astoundingly, his politics become the play’s politics.

What might Ms. Rebeck be trying to tell us with these gender-based insults and Jane Austen slurs? (Ignorant Jane-bashing is all the rage these days — just look at the critic Brian Sewell’s declaration that Austen is a “terrible bore” in a recent interview in The Guardian.) If this is a highly self-conscious way for Ms. Rebeck to smuggle in a feminist message to Broadway audiences, it’s so compromised as to be almost meaningless. We can’t read the playwright’s mind, but what’s onstage is a play that objectifies women and encourages the audience to ultimately empathize with their misogynist teacher. This message is expected from Mr. Allen; indeed, he’s celebrated for it, much as his characters are. From Ms. Rebeck, it disheartens — and does a lot more damage.

Were Kate given the last word, it would be quite possible to read “Seminar” as a sharp critique of gender inequality. She’s not mere window dressing like Izzy; she’s a good writer (once she dispenses with what Leonard calls her “sexually inadequate” twaddle and then fakes a memoir by a Cubano transvestite). And, as Ms. Rebeck reveals herself to be in that 2008 essay, she is a smart, weary realist when it comes to understanding how things work in the world.

But though she’s an adult, she’s not a capital-A artist. Ms. Rebeck only demands that we take Kate seriously up to a point. After she puts her panties back on at the end of the play, she explains to Martin why she is taking the ghostwriting job Leonard got her: “I think it’s a good start for someone like me.”

What to make of that “someone like me”? Does this mean a so-so writer? A woman? Is Kate a stand-in for her creator, who is, after all, not making great art but a witty, well-constructed Broadway play?

Leave the masterpieces to the Leonards and Martins of this world — her world — Ms. Rebeck seems to be saying. Once again, the girls all step aside.