Unfortunately, the audio interview is no longer available at all the links we had, so if anyone can extract it from the link provided in the source or elsewhere, we would be very grateful.

This is not a transcription, it is a translation from Ukrainian, but we believe that the essence of the interview has not changed. If anyone finds an audio file of this interview, we will be happy to transcribe it.

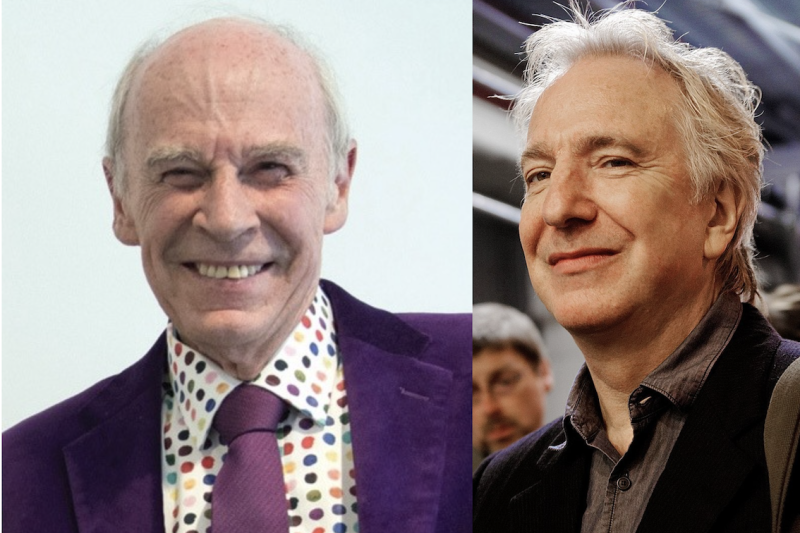

John Hannam: Alan, welcome to John Hannam Meets.

Alan Rickman: Thank you.

JH: This program is dedicated to the memory of Anthony Minghella. We’ll talk about Anthony and your extraordinary career. What would you say were his greatest qualities?

AR: I first met Anthony on the set of Truly, Madly, Deeply. It was his directorial debut. So, I think memories of someone working on a project that is so deeply important to them are ingrained on an emotional level. What stood out to me most were his human qualities. It’s not easy for a film director to admit vulnerability or even a lack of knowledge at times. I remember, on the very first day of filming, he turned to the crew and the actors and simply said, “Help me.” And of course, that instantly dissolves any defensive barriers. Anthony’s relationships with actors were always so human and essential to him. Of course, he was wise to bring in a group of actors he’d already worked with in theatre.

JH: That was definitely one of his strengths. You often see the same actors appearing in many of his films.

AR: He had a very strong sense of family overall. I think family was a constant source of inspiration for him—a kind of dynastic spirit. You were always surrounded by the Minghella family aura: Anthony, his sisters, brother, mother, father, and a crowd of children running around. And that was a source of immense… It’s still very difficult for me to speak about Anthony in the past tense, but family was at the heart of who Anthony essentially was.

JH: I know you’ve always been drawn to discovering new writers. But Anthony wrote this remarkable script himself, and that’s what drew you to the project, isn’t it?

AR: Yes, it’s usually the script that inspires you and awakens your desire to work. Of course, with some directors, you’d agree to read even a phone book, but… Anthony wrote the most compelling dialogue, and it was genuinely a joy to say his lines.

JH: When the filming was over, and it was a very low-budget production, there were rumors that it eventually grossed $20 million. What do you think about that?

AR: Well, yes. Though none of that money came our way.

JH: I’m so sorry about that. (both laugh) When filming wrapped, it was Anthony’s first film, and you played Jamie, one of the lead roles. Were you surprised by the worldwide recognition the film eventually achieved?

AR: Well, I think it was a bit of a slow-burn success. It’s fascinating to realize that this is still the film most associated with Anthony. And yet, you know, he was always in pursuit of truth. I think the simplicity and honesty of this film, and the fact that Anthony wrote it primarily for Juliet Stevenson, means that its essence and soul rest on a very solid foundation.

JH: I think everyone can see that. Would you say that this role was the closest to who you are as a person, out of all the roles you’ve played? Or not quite?

AR: Perhaps it was closest to who I was in 1991. But, you know, we’re meant to evolve over time.

(both laugh)

AR: Yes, probably. I felt very free. It’s such a luxury to simply listen and react, without worrying too much about layering on character traits.

JH: I have wonderful memories of the film, especially the scene where you play the cello after your return. Then your wife appears, and the two of you share that incredible moment. She’s a fantastic actress, isn’t she?

AR: Juliet is extraordinary. As I’ve said, we worked together extensively in theatre, and when we filmed that scene… she has remarkable intuition. She’s incredibly intelligent but also wonderfully spontaneous. I don’t know how you could rehearse a moment like that… We all rehearsed for about two weeks before filming, but that particular moment wasn’t rehearsed. And… well, how could it be? Anthony just placed cameras in various spots to capture whatever would unfold. Of course, I didn’t know this, and neither did she. So, what you see on screen is purely a display of instinctive acting.

JH: “Thank you for missing me.” Such a poignant line you deliver upon your return. A beautiful phrase.

AR: There are so many great lines in the film. I think Anthony always managed to avoid excessive sentimentality, consistently defying expectations. There’s a lot of humor in the film to leaven the emotional weight, if you will.

JH: Alan, in the two scenes where you play the cello, was there someone seated very close, actually playing for you? You were moving your hands, of course, but…

AR: My hand was always on the bow.

JH: Exactly.

AR: Everything else was done by someone else.

JH: Well, it was brilliantly staged. In the final scene by the window with the ghosts, when you see her with her new companion, I think that was one of the film’s most powerful moments.

AR: That’s usually when you hear animal-like sounds from the audience. Juliet and I got used to this at festivals. People behave themselves up until that point, and then they suddenly start sobbing uncontrollably.

JH: I’d imagine that if Anthony hadn’t passed away, your paths would have crossed again in the future.

AR: Oh… Who knows… That’s something you can’t predict or expect. Paths cross when they’re meant to, or when there’s a script that works for you. Actually, our paths did cross again for a Beckett short film featuring Juliet, Kristin Scott Thomas, and me. It was part of a program celebrating Samuel Beckett’s work organized by John Ford. We had such a great time reconnecting. Then there was a concert honoring Beckett in Reading—I believe that was three years ago.

JH: He was always so proud… always so proud of the ice cream on the Isle of Wight. Have you tried their ice cream?

AR: Of course.

JH: It’s wonderful.

AR: I know. A new flavor for every film.

JH: Yes. It’s fantastic. Shifting back from Truly, Madly, Deeply, which of Anthony’s films holds a special place for you?

AR: Of course, The English Patient has enormous significance for me. When Anthony was editing it, I was preparing to direct my first film, The Winter Guest. Anthony, being his usual generous self, invited me to San Francisco to observe him and Walter Murch as they worked on the edit. Again, I witnessed the deeply vulnerable phase of a director’s process. Anthony showed me a rough cut that was four hours long and allowed me to comment and ask sometimes quite basic questions… “Who is this woman? Where is she going? What’s behind that door? What is this building?” I think it was useful for him and Walter in terms of testing the narrative’s clarity. I was like a clueless audience member, repeatedly saying, “I don’t understand.” So, in a way, I became part of the process. It was absolutely fascinating to watch the world’s greatest editor and Anthony crafting what would become a legendary film.

JH: I know you attended the memorial service on the Isle of Wight. It was a beautiful day and a remarkable event.

AR: The weather was amazing, simply magical. It felt as though Anthony himself was orchestrating everything. I had a hard time getting there, and in the end, I flew by helicopter. From above, there was a stunning view of the incredibly beautiful country we live in. I flew back the same way. So yes, it was a very special day.

JH: We’re at the Concorde Hotel in Eastleigh. You were here yesterday as well, taking part in an event honoring Anthony, weren’t you?

AR: Yes, “honoring” in the sense that one of the choreographed pieces by Johnny Lunn, a great friend of Anthony’s, was set to a text written by Anthony. It was surreal to hear Anthony’s voice during the performance, and even more surreal to realize that he’s no longer with us. You hear his voice, and you think he might just walk in at any moment. It’s incredibly difficult when someone whose life is so intertwined with others, someone who exudes such positive energy, is suddenly gone without warning. It’s incredibly hard to come to terms with.

JH: He performed in this show at least six times because we’ve known each other for… oh, so many years. He was a huge fan of Van Morrison. I think it’s only fitting to play a Van Morrison track at the end of our conversation about Anthony. Would you agree?

AR: Absolutely.

JH: Let me quickly share a story Anthony once told me. He was at an airport—somewhere in Ireland, I believe. He had a new Van Morrison album with him and wanted to approach Van, have a chat, and ask for an autograph. But he couldn’t bring himself to do it.

AR: That’s a sweet story.

JH: In memory of Anthony Minghella, here’s Have I Told You Lately That I Love You by Van Morrison.

JH: Before the commercial break, we played a wonderful Van Morrison track. Now, let’s talk about Alan Rickman and your incredible career. Alan, you know, I’ve been interviewing people for… oh my goodness, over 30 years, and this is the first time I’ve met someone who shares my birthday: February 21st.

AR: Oh, happy birthday for the coming February!

JH: And a happy birthday to you! What I love most is…

AR: Do you know who else was born on that day? Robert Mugabe.

JH: Really? What I love most is that you didn’t come from a family of actors. Your father was a factory worker, an Irish Catholic, and your mother, from Wales, was a Methodist. It was a very working-class family, and acting wasn’t even on the radar.

AR: No, but my mother had a phenomenal singing voice.

JH: Really?

AR: Yes. And if circumstances had been different—you know, sometimes you just have to work to put food on the table—she could have been a performer.

JH: I know she was an extraordinary woman. Sadly, your father passed away when you were very young, leaving your mother to raise four children while working at the post office. That must have been incredibly tough for her.

AR: Of course, she didn’t have the luxury of choosing what she wanted to do. I think Britain holds a certain place in the world, but somehow we still cling to a class system. We’re surrounded by so many unsung heroes who raise children, feed them, and clothe them under extraordinarily difficult circumstances.

JH: As a child, you were drawn to calligraphy and watercolor painting. Were you always inclined toward the arts from an early age?

AR: Yes, I think children naturally gravitate toward what interests them. I recently saw a seven-year-old girl on TV hitting a tennis ball like a young Navratilova, just because she’d seen tennis on TV and realized she wanted to do it. Where does that come from? Yes, I picked up pencils, drew, and painted from a very young age.

JH: I know you performed in a few plays while at Latymer School. You did some acting there, didn’t you?

AR: Yes, I did.

JH: Did you feel an immediate pull toward the stage?

AR: Our school had a very strong tradition in drama. Our English teachers loved theater, and we always had school plays. After classes, we’d regularly gather to rehearse plays. Every year, there was a school production, and at Christmas, there was always a concert. There was always something happening. At the same time, the school was very academic, so there was a balance. When I turned 18, the question arose about where to go next: art school or university. Drama school wasn’t even considered, and as I now realize, choosing it at 18 would have been a huge mistake.

JH: The motto of your school was, I believe, “Slowly but surely,” much like your career, wasn’t it?

AR: Yes.

JH: Before becoming an actor, you worked as a graphic designer. Is it true you worked for the Notting Hill Herald?

AR: Yes. With David Adams.

JH: Quite a bold move, wasn’t it, getting involved with a new newspaper?

AR: It was one of the first free newspapers, and yes, I was part of it. There were no computers back then; everything was done by hand, late at night, unpaid, purely out of a love for the art and respect for their left-wing stance.

JH: My late father worked as a typesetter on a linotype machine, printing on metal. I remember watching him as a schoolboy. It’s amazing how much things have changed.

AR: We learned that in art school as well. We had to create posters manually and assemble design elements. So working with tweezers and tiny metal letters wasn’t new to me.

JH: As an amateur, you performed in Night Must Fall. Is that correct?

AR: Yes.

JH: At the Methodist Church Hall in Shepherd’s Bush?

AR: You know more about my life than I do! Yes, that’s right.

JH: At that time, you never dreamed… now we’re talking about your accomplishments, but back then, did you ever dream of a career on stage?

AR: I think I always knew what I wanted to do, but… everything in my life happened about ten years later than it might have. That’s just how it worked out. On the other hand, I approached directing with the experience of art school, and everything I’d learned came in handy when dealing with the visual aspects of filmmaking.

JH: In 1972, you took quite a bold step by auditioning for RADA. You performed one or two well-known pieces, didn’t you?

AR: I had to audition twice. The first time, I performed the soliloquy about the hollow crown from Richard II and a piece from a play by James Saunders. At my second audition… oh, why do I still remember this… I performed a piece from The Relapse, a Restoration comedy by Vanbrugh, and an excerpt from Long Day’s Journey Into Night.

JH: While studying at RADA, you worked for some time as a freelance dresser in the West End, didn’t you?

AR: Yes, that was after I got into RADA. Since I didn’t have a grant, I had to earn a living.

JH: It’s fascinating—Jeremy Irons, who was born on the Isle of Wight, also attended something akin to art school and worked odd jobs in the West End before becoming famous.

AR: Yes. I’d bet we’ve all done our share of unusual jobs at times.

JH: Is it true you dressed Sir Ralph Richardson and Sir Nigel Hawthorne?

AR: I never dressed Sir Ralph, but I did encounter him in the hallway and practically “fell to my knees”… I usually brought shirts to Nigel’s dressing room. Strangely enough, a few years later, I was performing on stage with them.

JH: Did you ever tell them about that?

AR: Oh, yes.

JH: You were an award winner at RADA. Were you a good student?

AR: Yes, I studied well enough, but I’m glad we’ve moved away from the prize system.

JH: Yes. Alan, two milestones appeared in your career quite early. Many people first saw you in The Barchester Chronicles, where you played Obadiah Slope, an ambitious clergyman.

AR: A heartthrob.

JH: Yes, a heartthrob.

AR: It was a very funny production. Alan Plater’s brilliant script (based on an equally brilliant novel) captured the internal political struggles superbly. All very humorous.

JH: Is it true that you modeled your character on a certain politician?

AR: I don’t think so. Who do you mean?

JH: I thought I’d heard you say once that you liked to satirize politicians you disliked. Just wondered if it was true.

AR: I can’t remember now. Maybe I said that at some point. Who might it have been back then? It’s been a while.

JH: That would have been sometime in the 1980s?

AR: Yes.

JH: You then appeared in a few episodes of Smiley’s People and later in Romeo and Juliet.

AR: The Romeo and Juliet film was my first TV movie, and I got it thanks to Alvin Rakoff, who took a chance casting a newcomer as Tybalt. Tybalt is a skilled swordsman, and suddenly he had to entrust a sword to someone who barely understood cameras, let alone how to act convincingly on film. It was very generous of him.

JH: In 1985, you performed in Les Liaisons Dangereuses with the Royal Shakespeare Company. That production was significant for you, wasn’t it?

AR: Incredibly so. It was an extraordinary production. We launched it with Juliet, Lindsay Duncan, Fiona Shaw, and Lesley Manville—brilliant, passionate actresses. Christopher Hampton’s legendary adaptation of Laclos’ novel premiered in Stratford, then moved to the West End, and later to Broadway. After that, my film career began.

JH: You played Valmont?

AR: Yes.

JH: Was it challenging to juggle between The Barchester Chronicles and that production?

AR: Not at all. I was having a great time. Back then, young actors still had to work in repertory theaters across the country. That system is now being eroded and destroyed by lack of funding and challenges like childcare. Repertory theaters can no longer afford large casts or ambitious productions. It’s damaging to theater’s life and vitality.

JH: Alan, during the days of repertory theater, you could perform one play, rehearse another, and read a third—it was wonderful, wasn’t it?

AR: Yes. Although, even working in Stratford, I performed in three repertory plays.

JH: Was it at the RSC that you met Ruby Wax?

AR: Yes, but that was when I first worked in Stratford in the late ’70s.

JH: Did you immediately notice her talent when you saw her on stage?

AR: Of course, she always had a certain brilliance about her. I remember she and another great actress, Darlene Johnson, put on a late-night revue. I think Ruby always carried her star with her. She called that revue the Johnson-Wax Show.

JH: Very clever. And have you followed her career with great interest since then?

AR: With both interest and involvement. I directed her at the Edinburgh Festival, and later we worked together on her One Woman Show in the West End.

JH: On Broadway, you were noticed and invited to act in films, suddenly finding yourself in a movie with Bruce Willis. That wasn’t the kind of first film you’d dreamed of, was it?

AR: Probably not, but it turned out to be a kind of classic. Not a day goes by without it being shown somewhere. It’s the best of its kind. If you look closely, every Black character in it is a positive figure. There’s a lot of humor, and the visuals are excellent. It’s a very simple story, very well told. But, of course, it wasn’t what I expected. I never thought I’d build a career in film. I just followed my destiny.

JH: Hans Gruber as a character quickly gained worldwide popularity.

AR: You don’t really think about that—you just make the film and try to invest meaning in your work. Perhaps my ignorance played a role again. I knew nothing about filmmaking and approached the role as I would in theater. The director was a bit surprised when I asked questions like, “Who is he?”, “Where does he come from?”, “What’s his backstory?” and so on. My question, “Why is he dressed like a terrorist?” ultimately led to my character wearing an elegant suit.

JH: Have you seen Bruce Willis since then?

AR: Yes, I hosted an event in his honor in Los Angeles six or seven years ago.

JH: I don’t know if it’s true, but I once heard you say, “I got the role because I was cheap.”

AR: Yes, I did say that. It’s true.

(laughs)

JH: Well, being cheap worked out. That was your starting point.

AR: Yes, absolutely.

JH: After that, you returned to star in the BBC television production Benefactors (1989). How different were these two roles?

AR: Very different. Well, you always aim to immerse yourself in a great piece of literature, in this case, Michael Frayn’s play. And working with Harriet Walter, Barbara Flynn, and Michael Kitchen was a gift.

JH: Michael Frayn is a brilliant writer, isn’t he?

AR: Incredible. Especially for actors.

JH: In Hollywood, you appeared in The January Man. Do you recall that fondly?

AR: I recall everything I’ve done. If someone asks me, “What’s your favorite film?” I’d say I don’t have one. Filming takes six weeks to three months of your life. You remember what happens behind the scenes—visiting other countries, being a bit of a tourist when circumstances allow. Certain moments behind the scenes are unforgettable, as are the friendships you form. Pat O’Connor, the director of The January Man, and his wife Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio became some of my closest friends in London. Ultimately, you don’t judge a film by whether it was successful or not.

JH: You were in Australia too, starring in an Australian western.

AR: Yes.

JH: Quigley Down Under. That must have been fantastic, wasn’t it?

AR: Alice Springs was absolutely incredible. And again, I made many close friends during that film.

JH: The music video In Demand by Texas featured my guest, Alan Rickman. You actually danced with Sharleen, didn’t you?

AR: I did. It was very thrilling.

JH: I can imagine.

AR: At six in the morning, at a gas station somewhere on the outskirts of London.

JH: For actors, that’s invaluable. It opens doors to a different audience.

AR: Well, you have to broaden your horizons a bit. To be honest, it was incredibly flattering. Sharleen Spiteri calls and asks, “Will you tango with me?”

JH: Not many men could say no to that.

AR: I could have.

JH: Alan, 1991 was a remarkable year. We’ve already discussed Truly, Madly, Deeply in detail—an extraordinary film. Then there was Close My Eyes and Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves. In 1991, these films secured places in the top ten Hollywood releases.

AR: I can’t believe the first two made it into the top ten in Hollywood. In England, they didn’t receive that level of attention, but they certainly weren’t overlooked either.

JH: Barry Norman named you British Actor of the Year on his show.

AR: I wouldn’t know. I don’t keep track of that. Thank you, Barry Norman.

JH: I recently rewatched Robin Hood. It’s undoubtedly a Hollywood movie—not particularly outstanding—but I think one of its strengths was the Sheriff of Nottingham, where you delivered such a virtuoso performance. Was it intended to be that over-the-top?

AR: That was my most subtle work. I’m delighted to hear that there’s a film planned called Nottingham about the Sheriff, with Russell Crowe in the lead. I could give him a few tips.

JH: You had lines like “And make the stitches small” and something about Christmas.

AR: I said, “Cancel Christmas.”

JH: Do you enjoy playing such roles? Did you have fun working on such a big production? Was it enjoyable on and off set?

AR: Yes. Although working on a film with such a massive budget is an entirely different world. There are always people hovering around, calculating expenses, with pens in hand and panic on their faces. Everything is so expensive, and having fun is the last thing on their minds—they just need you to stay within the budget. I really enjoyed working with Kevin Reynolds and Kevin Costner, though I only met the latter toward the end of the shoot during the sword fight scene. Working with Geraldine McEwan was fantastic.

JH: Your pairing must have been wonderful.

AR: It was incredibly delightful to see such a renowned and genuinely celebrated actress like Geraldine, with one eye and a spooky wig, having the time of her life.

JH: You won a BAFTA for that film, didn’t you?

AR: I did.

JH: Were you surprised?

AR: Well… I don’t know. I was just happy to see that there’s a future for unrefined performances too. Apparently, it’s okay to be vulgar sometimes.

JH: You also participated in a film like Mesmer by Tim Robbins. What was that experience like?

AR: Very positive. It was Tim Robbins’ debut as a director. I like the idea of actors stepping behind the camera when they have the talent for it. God knows there are plenty of examples in history.

JH: Sense and Sensibility is my unwavering favorite among your films. I’ve watched it countless times. You played Colonel Brandon. I’ve always loved period dramas, and I consider this film a masterpiece. Do you think costume dramas are making a comeback?

AR: Did they ever really go away? Perhaps in terms of emotions. When Emma Thompson writes the screenplay and Ang Lee directs, these two will look at Jane Austen’s world through slightly different telescopes. Both of them, like Anthony, are searching for truth.

JH: This film was a fantastic opportunity for you to break away from previous archetypes, like the villain. The role was entirely different—everyone sympathized with you.

AR: Well, he’s 110% a good man and 120% a complete character. Sometimes, when playing a role, it’s helpful to narrow your focus.

JH: I loved the small scene where you don’t even say anything: you bring flowers, and there’s Willoughby, also with flowers. It’s a beautiful moment. You turn your head to see what flowers he brought.

AR: Along comes a handsome, young, dark-haired scoundrel with a bouquet.

JH: The scene where you tell Miss Dashwood the truth about Willoughby is marvelous. You selflessly reveal the truth about your past.

AR: That scene brought its own challenges. It wasn’t shot on a set but in a real house, and the poor camera crew struggled to move around the cramped space, avoiding mirrors and other interior details.

JH: The film ends with a wedding—a double wedding. How long did it take to film that scene?

AR: I think just one day. Unfortunately. Everything went so smoothly with that film, especially the weather. I was even nicknamed “Captain Weather” at the time because I’d sit in the hotel waiting for the sun to hide so we could film certain scenes. That film seemed bathed in a golden glow. You know, living in England, the weather is so unpredictable.

JH: Had you ridden horses before this film?

AR: Not much. Occasionally, but I had ridden. We work with people, but there’s no such thing as a predictable horse.

JH: No, there isn’t.

AR: Sitting on horseback, you hold the reins and cross your fingers simultaneously.

JH: The film Rasputin earned you an Emmy. Another success.

AR: That was a unique experience. Most of the film was shot in Saint Petersburg [note: lowercase used intentionally]. Then, as various difficulties arose… It was a hard time in Russia—it became difficult to film and feed the crew—so we had to move to Budapest earlier than planned. It’s fascinating to play someone who was once so demonized. If he were alive today, he’d probably have a successful clinic on Harley Street.

JH: When playing certain characters, you naturally do your “homework” and study the material. Are you drawn to the personality of the character, their story?

AR: Absolutely. You start to realize how often people are judged with extreme bias. That was the case with De Valera in Michael Collins. So yes, I’m making up for all the time I slept through history lessons in school.

JH: Alan, you’ve turned down many roles over the years. I know you passed on offers for films like Carrington, The Lion King, Vito, and GoldenEye from the James Bond franchise.

AR: Oh, not quite.

JH: No? Alright. Newspapers don’t always tell the truth. Which offers did you actually turn down?

AR: “Turned down” sounds terribly arrogant. I wasn’t offered anything for GoldenEye. As for Carrington, I simply chose not to do it. In both theater and film, you have to make decisions, especially if you don’t want to do something you’ve recently done. For instance, if you’ve just spent six months in the theater, you might not want to commit to another play right away because you’re tired and need a break. So we say no for a variety of reasons. There’s really nothing to regret about it.

JH: During your streak of villainous roles, did you turn down some because they were too similar to previous ones? Were you worried about being typecast?

AR: The thing is, if you count them up, the actual villains are in the minority compared to the complex, multifaceted, and ultimately good people. It’s just that some films have bigger advertising budgets and get more attention.

JH: You participated in Tubular Bells II.

AR: Yes.

JH: In the number with the bell.

AR: It was fascinating. It felt like a journey back to my youth.

JH: By participating in Tubular Bells and similar projects, you’ve engaged with popular music.

AR: I appeared in a music video and contributed to a few albums.

JH: Severus Snape from Harry Potter. You’ve acted in all the films.

AR: I prefer not to discuss Harry Potter because there are always children who are just reading the first book. They might hear something they’re not ready to know yet.

JH: Taking on something new often brings you new fans.

AR: Actors are grateful if anyone wants to see the results of their work. However, there’s something special about a child meeting someone connected to the images they’ve formed after reading the book—or, unfortunately, just from watching the DVD. You can see how they’re mentally putting things together, matching their imagination to reality.

JH: The film Love Actually breaks tradition too. It’s quite a different type of role for Alan Rickman.

AR: Yes, he’s an ordinary man. An ordinary man who cheats on his wife.

JH: I love the scene where you’re buying a necklace. Your duet with Rowan Atkinson as the salesman was brilliant. Was it fun to shoot that scene?

AR: It was, but the filming took place at night in Selfridges, and by the end, both of us were barely standing. Of course, shooting at night made sense. By 6 a.m., we had to clear out so the store could prepare for regular opening hours. But the mind doesn’t always cooperate with the body.

JH: Films like that seem to have a massive audience.

AR: Richard Curtis has a knack for captivating viewers. I think he shuns hypocrisy and self-satisfaction in people.

JH: Let’s talk about directing. You mentioned your work on The Winter Guest in 1997. You also directed the play My Name is Rachel Corrie, which had great success in the West End and earned you an award. Do you plan to continue in that direction?

AR: I think it’ll be a balance. I’m not directing at the expense of acting. But directing is an important part of me. In August, I’m directing a play at the Donmar Theatre, and next year, I’ll direct a film. So yes, I’ll continue to direct.

JH: You’ve worked with many great directors, such as Anthony Minghella. Have you learned anything from them during the process?

AR: I think so. I watch them and envy their confidence and courage in making decisions, because that’s the essence of directing. You have to make decisions a thousand times a day. People come to you with questions, questions, and more questions. They need answers, answers, and more answers. Without them, the process grinds to a halt. I’ve mentioned the assistant producers standing on the periphery of the set with a stopwatch or a checkbook.

JH: Do the breaks in filming bother you, or have you grown accustomed to them?

AR: Oh, I love breaks.

JH: Really?

AR: They’re almost a hobby for me.

JH: In Die Hard, you probably had only about eight lines a day.

AR: Probably, but back then, everything was new to me. And there was always someone to talk to. It’s wonderful when you’re listened to and heard.

JH: Looking back, what do you think about the balance between your work in theater and film? After all, film actors sometimes need the nourishment of live theater.

AR: I’ve probably done little theater work over the past ten years. The thing is, theater requires your commitment far in advance, whereas with film, you need to be ready to shoot by next week. The demands don’t align well. It’s ideal if the filming schedule is locked in and you know there’s a gap of six weeks when you can perform in the theater. Theater is like a religion. Or like the gym. If you don’t go, your muscles weaken.

JH: The pay isn’t as good, of course, but live theater is hugely significant.

AR: Not for everyone. For me, it is. Theater is incredibly important to me.

JH: In 2002, you performed in Noël Coward’s brilliant play Private Lives, both in the West End and on Broadway. Are there differences between London and Broadway audiences?

AR: Yes, there are. You just have to sense them. With Noël Coward’s work, sometimes you need to adjust the pronunciation of certain words, or the audience simply won’t understand. Sometimes, you have to tweak the rhythm slightly. In New York, the audience is very quick-witted. In some ways, it’s a more theatrical city than London, possibly because London is so sprawling. Manhattan is very compact. If your play is a hit in New York, you’ll know it just by walking down the street.

JH: You had the chance to debut on Broadway. On Broadway, it’s much easier to be noticed by people in the film industry compared to the West End.

AR: Yes, the entire film industry is centered here.

JH: One of your later films was Sweeney Todd. Before we dive into that… I watched it on Thursday evening, and on Friday I usually buy…

AR: You avoided butcher shops entirely.

JH: I always buy meat pies, but this time, I couldn’t bring myself to even look at them.

JH: For you, this was a different format—a musical.

AR: Yes. I had done pantomimes and musicals before, back when I worked in repertory theater. Early in your career, you do what you’re told. Filming this was such a joy because it was, above all, Tim Burton, Stephen Sondheim, and Johnny Depp. Pure pleasure. Once you’ve learned that damned song.

JH: You sing it twice.

AR: It’s a tricky song. Sometimes your brain tells you it’s going to be one note, but Stephen Sondheim says, “No, it’s this note here,” half a tone higher or lower. It’s hard to commit to memory.

JH: Tell us about your role at the film’s climax. It’s filmed so realistically. I know you won’t reveal how it was done, but the death scene looks incredibly real.

AR: On set, it was anything but realistic. I’ll tell you how it was shot. Of course, there was prosthetic makeup and tubes on my chest connected to hand pumps just out of frame. Also, to ensure proper color correction later, the blood was bright orange and mixed with sugar—just in case you accidentally swallowed some.

JH: Did you enjoy playing Judge Turpin?

AR: I did, though it wasn’t easy since he’s such a cruel character. There aren’t any likable people in the film, really. It was a sort of competition for who could be the most unpleasant. But I tried to portray the judge as still resembling a human being.

JH: I think one of the best reviews of the film came from the U.S., describing your character as “radiating arrogance and moral decay.”

AR: That’s accurate, yes.

JH: Do you plan to take part in other musicals?

AR: Not for now, but one should never say “never.”

JH: May we talk about your upcoming projects? I know you have two films coming out.

AR: Yes. In a few weeks, I’m heading to the U.S. for the premiere of Bottle Shock. It’s a wonderful film based on true events from 1976 when, during a blind wine tasting in Paris, American wines were declared superior to French ones.

JH: Really?

AR: Yes. It’s a charming American film—funny and stylish. In the fall, another film, Nobel Son, will be released in the U.S. As I mentioned earlier, in late August, I’ll begin directing a Strindberg play at the Donmar Theatre.

JH: Fantastic. That theater produces incredible work, and so many stars take part.

AR: Just amazing actors and productions. Actors love performing there. You know, you’re not tied down for six months straight; you can do a run and then move on to something else.

JH: If you hadn’t gotten into RADA, how do you think your life would have turned out? Could you have been a successful designer?

AR: I think I was lucky to part ways with set design. We were very successful—not financially, but creatively. We formed a design group and quickly reached quite a high level. However, we knew nothing about running a business. No one got rich. For me, it meant the chance to move on. I thought, “What’s next? Nothing’s going to change.” And then an inner voice said, “You’ve always wanted to be an actor.” So… I don’t know. You either push your life forward or follow your instincts—it’s one or the other.

JH: Alan, on the Isle of Wight, there are aspiring theater enthusiasts. Many of them perform in Anthony’s plays. What advice would you give them? You were an amateur actor who grew into a top-tier professional.

AR: Working in amateur theater can be wonderful. It should be interesting and fun. The word “play” in Beckett’s Play has a double meaning. It’s a production, but it also involves storytelling. Humans always have a need to share stories. The less your ego gets in the way, the better you see your role in the storytelling. The more you feel like an instrument finely tuned to its purpose. Make sure you can run 100 yards without losing your breath. Make sure you’re breathing. If you can’t breathe, you can’t speak. Just prepare your instrument for storytelling and play.

JH: Alan Rickman, it’s been a pleasure speaking with you. Thank you so much for your time.

AR: Thank you.

JH: I wish you tremendous and ongoing success in your career.

AR: Thank you.

JH: Today, we remember our mutual friend, the great Anthony Minghella. We’ll never forget him.

AR: The wonderful thing about films is that they remain forever. All of Anthony’s work gives viewers something to think about.

JH: Best of luck, and thank you so much.

AR: Thank you.