By Heather Lawton – The Guardian

Alan Rickman concedes that heavy metal fans and theatre audiences are often worlds apart. Perhaps this shouldn’t be the case. Rickman refers back a few years to when he was performing in Man Is Man at Bristol’s Little Theatre. Having taken his final bow to the discreet Brechtian audience, he took a look in the next door hall where Thin Lizzie was performing.

“I just opened the door and was thrown back by the high-octane excitement that was going on on that stage. And you thought now just a minute…I’m not trying to be a rock group and we don’t have to have people watching us waving scarves in the air and jumping up and down. But there’s got to be a version of that excitement, otherwise theatre is a waste of time.”

Excitement is hard to come by. Rickman says he’s found it in Peter Brook’s work and at Ariane Mnouchkine’s Theatre du Soleil on the outskirts of Paris. Having seen Henry IV there, and more recently her play on Cambodia, The Terrible But Unfinished History of Norodom Sihanouk. Rickman registered the experience of “an entire audience actively involved in the story unfolding in front of them” and of feeling “parts of you being activated while you’re watching it that seem only to be activated when you go to wonderful theatre.”

This is the reason he’s glad now to be doing something of Mnouchkine’s. He opens as Hendrik Hofgen in her version of Klaus Mann’s Mephisto at the Barbican tomorrow. Adrian Noble directs this new translation by Timberlake Wertenbaker. A translation faithful to Mnouchkine, says Noble, who describes the play in her words, as a “histoire exemplaire.”

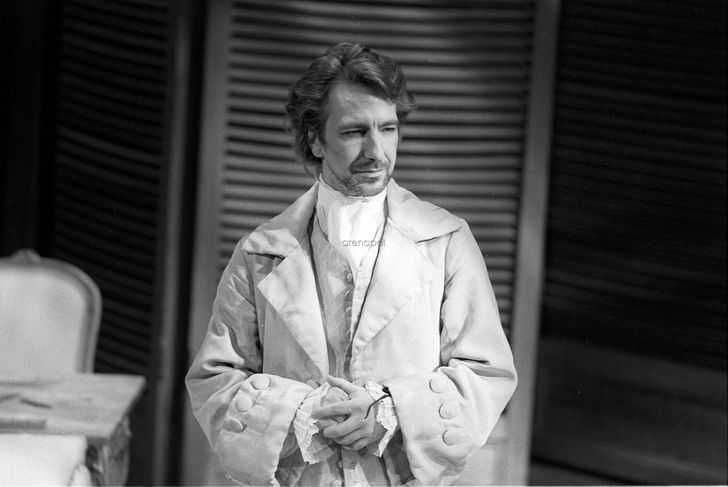

Doing Les Liaisons Dangereuses, Rickman sometimes felt “a lack of breathing in the audience” – a version perhaps of his own excitement at Mnouchkine’s theatre. In the RSC’s production of Christopher Hamptons’ dramatization of the Laclos novel, Rickman played the morally bankrupt Vicomte de Valmont with superb, sexy, dissolute languor, plus a brilliant sense of timing and feeling such that it was tempting to say perhaps it was a professional turning point for him. Not a suggestion he relishes – all acting is cumulative. He shrugs. “With a part like that, you’d be a fool not to use it.”

Rickman sees his part as Hofgen as being about “how big a trough you can dig for yourself,” should you be blinded by hideous, meaningless ambition. Mnouchkine’s work requires a somewhat heightened form of acting, he says. She provides more of an over than a sub-text, requiring a fairly direct and energized style.

When Mephisto, the story of an actor’s gradual corruption in Nazi Germany was performed at the Theatre du Soleil in 1979, it caused quite an uproar. More than 200,000 saw the play, seated with stages around them so they could turn from Hamburg to Berlin with a mere swivel.

One of the reasons perhaps for the play’s impact may have been that the novel (written in 1936) was still embalmed in litigation and banned in Germany. It didn’t appear legally there until 1981. Istvan Szabo’s fine adaptation was the same year. Thus the story of Mephisto – now well documented – was until comparatively recently a tale one had to burrow for under bookstalls by the Seine to find illegal German translations.

It was like seeking out a Nabakov or a Genet, but the reason for the prohibition was libel rather than indecency – the character of Hendrik Hofgen is extremely close to the German actor Gustaf Gruendgens, Mann’s brother-in-law, and known for his role as Mephisto in Goethe’s Faust.

Despite allegations of Nazi association, Gruendgens remained an actor of significance in post-war Germany until his suicide in 1963. It was his adopted son who brought the libel action.

Klaus Mann committed suicide in a Cannes hotel in 1949, aged 43. A contributory factor may well have been his failure to get Mephisto published in post-war Germany. Mnouchkine’s play opens with a voice speaking a letter of rejection from a publisher to Mann, followed by Mann’s bitter reply. And indeed one of the last letters Mann wrote before his death was a savage indictment to a publisher who had reneged on his promise to publish the novel.

Rickman is reluctant to be weighed down by autobiographical associations. Having read the novel, Mann’s autobiography the Turning Point, history books and having seen the movie, he says one should assemble the information but then “throw it over your shoulder and just do it.”

The process is not dissimilar, he says, from confronting a speech like the Seven Ages of Man from As You Like It (also directed by Noble). “It’s one of the most famous speeches in the world and you can’t pretend it isn’t – in a way, it’s got neon lights around it and it doesn’t spring naturally. So therefore, it needs a sort of artifice. Gradually over the year, I hope I’ve started to find a balance between keeping it as part of the scene but also giving it what it was asking for.

Mephisto, the play differs from the movie, says Adrian Noble, because it is not a biopic, but a play which concentrates on an ensemble, a community of actors, representing different forms of choice under extreme situations. “Each scene requires particular qualities of energy and focus of political debate on stage which is rare, in the English tradition. It’s thrilling to work on because it requires a new vocabulary with which to tackle it and different routes to achieve an end,” says Noble.

Does the production offer parallels with other societies, Britain maybe? (unemployment figures chart the text and there are references to dead elms). Noble and Rickman both say the information lies within the text and it is up to the audience to decide whether it’s relevant. “Here’s the raw material of how change happened in a society when people said this couldn’t happen. But that’s no reason not to keep looking at how a sequence of events can occur in a supposedly free country,” says Rickman.

What have been turning points in Rickman’s life? The most important, he says, was his decision, aged 26, to renounce a career as a Soho-based graphic designer and go to RADA. Another was to leave Stratford seven years ago after only a year there (playing in The Tempest, Captain Swing, Antony and Cleopatra).

He then worked at the Royal Court, the Bush and Hampstead Theatre Club in plays like Dusty Hughes’s Commitments and Bad Language, Snoo Wilson’s The Grass Widow, Aphra Benn’s The Lucky Chance.

If acting is a cumulative experience, Rickman sees a visit to russia with The Brothers Karamozov as important. It was an extraordinary time, culminating in a performance in a 7th century church in Tbilisi, with the four players singing Ode to Joy and climbing into this strange steeple on a hilltop. While there he saw a lot of theatre, including an Estonian theatre company doing Edward Bond’s Bingo in moscow.

If the character Hofgen ends the play with the words “I’m only an actor”, the actor Rickman would disagree. “I’m only an agent, a middle-man. But a very powerful one because you can influence and alter, help or subvert, or encourage or expand what the author is trying to say.” Scripts or texts which cartoon serious issues and character, with politically unsound messages which don’t help anyone, should be avoided with a barge-pole, Rickman says. He cited White Nights, which he read for. For such work he quotes Dorothy Parker. “This is not a script to be tossed lightly aside. It should be hurled with great force.”