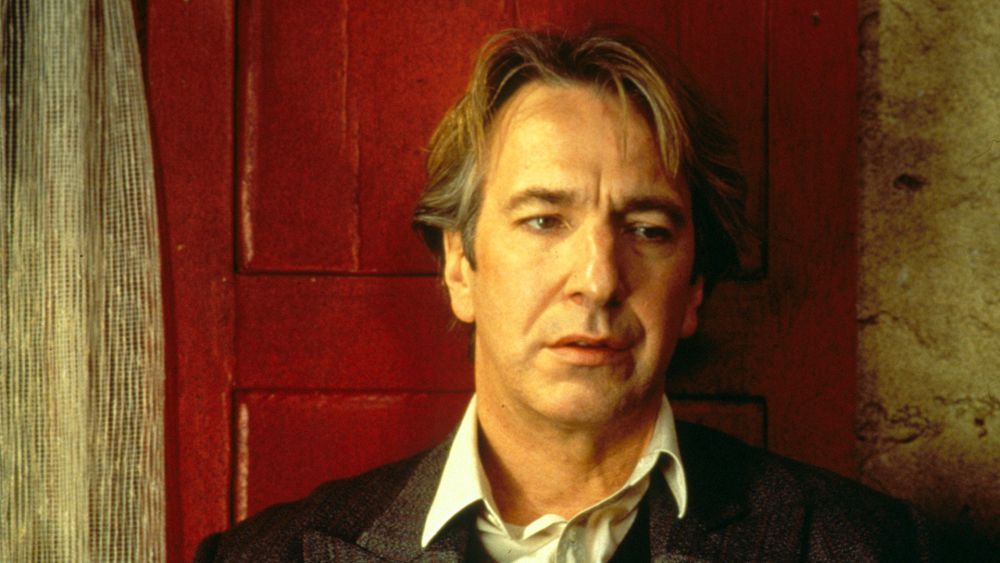

COLD SMOULDER

by Valerie Grove

Harper’s and Queen (magazine) – April 1995

The slanting slavic eyes that can glitter so threateningly give Alan Rickman a sinister and brooding presence on the screen; but in a hotel in Holland Park he pours out a friendly cup of tea without showing a shred of menace. What makes him so jolly hard to pin down is that he never does the same kind of thing twice.

His cinematic impact is very particular. Until he arrives on the screen in An Awfully Big Adventure, Mike Newell’s film of Beryl Bainbridge’s tale of a stage-struck girl in a local rep theatre in wartime Liverpool, Hugh Grant appears to be the romantic interest. Then whoosh, O’Hara (Rickman) arrives like the bad guy in a Western, roaring up north on a motorbike with a backpack, rendering every other male character, including Grant, insubstantial and homouncular next to Rickman’s enigmatic but definitely macho physical presence.

The rise of Alan Rickman was not meteoric, so when he first came within the popular gaze he already had a vintage lived-in look. Before he became an actor at all, he had another life altogether. At Latymer Upper School in Hammersmith (an ancient, independent foundation whose old boys include Hugh Grant, Mel Smith and George Walden, MP) drama and performance were encouraged: every Christmas boys and masters took part in a revue called ‘Chantaculum’. It was his form master, the late Colin Turner, who propelled him on stage at the age of eleven: Rickman’s performance as Volumnia, mother of Coriolanus, was thought memorable But acting as a career was not considered. He thinks it is mad to have to make lifetime decisions at that age, but when torn between an English degree or art school, he heard a small, quiet voice inside his head (the same voice which, in a restaurant, tells you to have fish and salad, while ‘this wild bruiser of a will’ goes ahead and orders regrettable things instead) telling him that art was what he should do. He went to Chelsea Art College, then to the Royal College of Art and set up a design company called Graphiti in the late Sixties. They designed LP sleeves, book jackets and a subversive left-wing free-sheet with the misleadingly conventional title of the Notting Hill Herald. They had a studio in Berwick Street, in the heart of Soho: ‘with white walls, sanded floors, trestle tables and no capital … and it was very heaven’.

So how do you throw up graphic design and go to RADA? ‘You get a piece of paper and a pen,’ Rickman says patiently, in his slow, laid-back voice, ‘and you write, “Dear RADA, please give me an audition”. And you watch yourself putting it in an envelope, sticking a stamp on it and putting it in the letter box. And you watch yourself doing these things because you have set in motion events which will change your life.’

When I voiced surprise that anyone could walk into RADA off the street and audition, he said, rather crossly, why shouldn’t they? That was how it should be. ‘It’s bad enough now that RADA is going to become just another finishing school, because grants are becoming so difficult only people who can afford to go will go.’ I said anyone going into journalism (he tends to voice a ritual irritation with all journalists) would at least have written something first. ‘Of course, there is more to it than just walking on to a stage. And the acting profession suffers from not getting as much support or respect for its training as dancers or opera singers, neither of whom would dream of walking on to a stage without working on the instrument.’ Quite.

At RADA he won every prize going. Then followed years at Bristol and with the RSC. Thus he was in his mid-forties by the time he played Juliet Stevenson’s importunate ghostly boyfriend in Truly Madly Deeply, and gave the Sheriff of Nottingham such amusing overtones in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, and was named Best Actor in the Evening Standard Film Awards.

Last year, BBC2’s The Late Show ran a programme devoted to Rickman, filmed in Hungary during the shooting of Mesmer, his first leading film role as the eighteenth-century visionary healer, scripted by the late Dennis Potter. What came across was his intelligent and painstaking immersion in the role, and the intensity of his approach to every detail of the film’s development. (It is entirely in character that Rickman enquired why the cast of Hungarian extras, masquerading as the cream of Viennese society in powdered wigs, had been given only bread rolls for lunch while the cast had hot food). But you have not seen Mesmer yet, because it is locked away in a dispute with the distributors. Rickman was caught, during The Late Show documentary, gloomily prophesying exactly this. What went wrong? ‘It is possible they were expecting a more commercial film … with a different ending, a happy ending,’ he says. At Potter’s memorial service, Alan Rickman read from Mesmer’s words; and the next day found himself saying the same things at an arbitration meeting with the film’s distributors. So we must wait to be mesmerized by that performance.

Meanwhile, on to something completely different. The first play he has directed, Sharman Macdonald’s The Winter Guest – elliptical, elegiac, gently moving and funny – has just opened at the Almeida Theatre in London after first airing at the West Yorkshire Playhouse in Leeds. Rickman was himself largely responsible for its being written. As a script-reader for Jenny Topper at the Bush Theatre in the early Eighties he first spotted the potential of Macdonald’s When I was a Girl I used to Scream and Shout, submitted under the pen name of Pearl Stewart. Later he introduced Macdonald to Lindsay Duncan, his co-star in Les Liaisons Dangereuses. ‘Lindsay is wonderful raconteur, a great natural wit and an immensely compassionate person, and she used to tell stories about her mother, who had Alzheimer’s, that were sad and funny in equal measure.’ The result is The Winter Guest, with Phyllida Law (Emma Thompson’s mother), who gives an exquisite performance as the mother.

Two hours after the curtain came down on the first night of The Winter Guest in Leeds, Rickman was on his way to Gatwick for a flight to Dallas, then to Salt Lake City and the Sundance film festival to launch An Awfully Big Adventure to the American press. After this jet-lagging journey he was disgourged outside a cinema at night in a snowbound street, and as he tried to enter the cinema a heavy hand stopped him and said, ‘Hey where’s your ticket?’

He laughs. Filming has come ‘like a great present’ in the last six years. It has improved his stage work, he thinks since: ‘You become better acquainted with stillness. On film you put all your energies into a single glance.’ That is certainly true in An Awfully Big Adventure; but to say more would be to divulge the denouement.

After the farcically gripping Die Hard in 1988 everyone assumed he would be lost to Hollywood. Hans Gruber was a cartoon character (‘You didn’t wonder what he had for breakfast did you?’) though it must be said, he played him admirably. ‘My life became a cartoon too at that point. I’d just finished on Broadway doing this tough play [Les Liaisons Dangereuses] and suddenly I moved from the dark into the neon light.

‘It was great fun to do, and the offers did roll in. But you don’t always want to do the same thing again. A life of endless repetition wouldn’t make sense at any level.’ But it made his name bankable enough to let him choose what he wants to do, based almost entirely on a good script: ‘You either want to say those lines, or you don’t.’

In 1992, he was a notable Hamlet at the Riverside Studios. ‘Darling,’ says Thelma Holt, his producer, ‘I’ve seen more Hamlets than I’ve had hot dinners; I spent eighteen months of my life playing Gertrude. I know that play better than any other, and with no disrespect to any of my other Hamlets, Alan Rickman was the Hamlet of my life. He did something rare: he told a story, and it was as if it was a new play. People always wonder what will he do with “To be” and “Rogue and peasant’; yet I could not have predicted how he would say them. Everything was new.’

In the same year, by contrast, he directed his friend Ruby Wax in her one-woman show, Wax Acts. ‘People assume she just stands at the mike and delivers routines.’ he says. ‘But she is the most deeply serious person about her work, tussling with very personal material about herself and her parents. It was achingly funny but you can’t be alone on stage for two hours without a sense of structure and a lot of bloody hard work.’

He is a political animal but when I invite him to talk about his politics he says simply ‘No’. He explains that he feels superstitious, because of what happened just before the last election when Labour’s hopes were so unexpectedly dashed at the eleventh hour. ‘I’m watching to see how the Left will redefine itself. But I feel I’m looking down the wrong end of a telescope. I can’t quite see it’s shape, so I’m not going to talk about it.’

His political views inform all he does: Thelma Holt says his sense of social justice makes him a humane actor and a generous director. He welcomes the change in the council of Equity, the actors’ union: ‘Equity really is a microcosm of the country: the twinset and pearl brigade right next to the jeans and T-shirts, people of all ages involved in the same activity. Now we’ve got Michael Cashman and Charlotte Cornwell on the council, so a compassionate voice is there and things are really changing.

‘But I feel superstitiousness, a watchfulness and a nervousness about whether the sea change will happen in the country as a whole. If we don’t change, almost for the sake of change, then I really believe this is an exhausted nation.’

He is one of the few of his generation who has managed to avoid picking up at least one wife and several children and a dog along the way. He guards his private life with ferocity – hence our meeting on neutral ground – reasoning that no actor’s professional standing is enhanced by having his domestic life exposed Hello! magazine-style. ‘It’s so unfair on the people involved. She [his partner, an academic] has nothing to do with all this. And I really resent it when her name gets mentioned. It makes life hard for her.’

I am reminded of Dame Edith Evans who once responded ringingly to a reporters’ question about her husband: ‘It is not of the slightest interest to anyone but myself, to know to whom I am married.’

He says he is ‘still living the life where you get home and open the fridge and there’s half a pot of yoghurt and a half a can of flat Coca-Cola.’ Prolonging a student lifestyle beyond all chronological probability? ‘It’s just a life on the move, really, and that’s the way I prefer it. I like to present a moving target.’ He has been on the move so much he is the only person in the world who has not yet seen Mike Newell’s previous film, Four Weddings and a Funeral. ‘Nothing gives me as much pleasure as travelling. I love getting on trains and boats and planes.’ He made Quigley Down Under partly because he wanted to see the Australian outback. He went to Russia with The Brothers Karamozov. The Liverpool of An Awfully Big Adventure was recreated in Dublin ‘where I was very aware of being a Celt in the land of my ancestors. My blood is awash with Welsh and Irishness which probably explains a lot about a lot.’ Meaning? ‘What I hope it means is being not closed.’

The camera loves him. ‘I can’t stand watching anything I’m in, so I have no opinion about that. All I think about acting is, the camera likes you if it can see you thinking and most importantly, listening. All you are is this bundle of half-formed instincts and inadequate technique, aiming itself at the project, hoping something identifiable forms … and hoping it will involve the audience. You hand yourself over to the medium. I think there’s some connection between absolute discipline and absolute freedom. When I am asked about influences, I always say I bow down to Fred Astair, because when you look at him dancing you never look at his extremities, do you? You look at his centre. What you never see is the hours of work that went into the routines, you just see the breathtaking spirit and freedom.

‘At the end of The Tempest, when Prospero lets Ariel go at the same time he chains Caliban to him, I think Shakespeare was saying something about the creative act: and of course it’s impossible to do, but it’s worth having a go at it. The greatest singing and dancing and painting is the freest and simplest, and there is years of work behind it. It’s the same with Picasso, Matisse, the Japanese scroll painters – it’s not just sloshing colour on a piece of blank paper, it’s the tiny, disciplined muscles creating a single brushstroke.’