Acting against expectations

by Hugh Linehan

The Irish Times – May 5, 2001

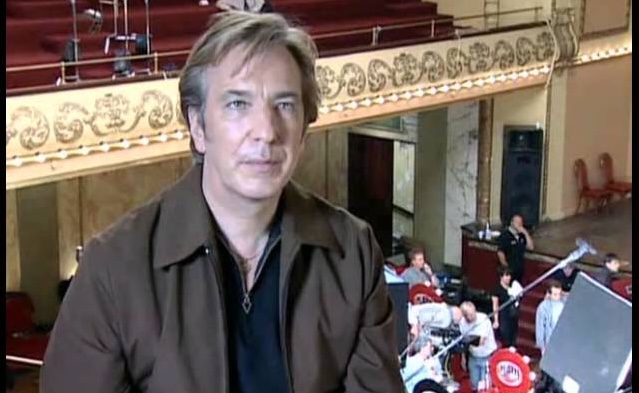

Although he’s known for his portrayal of villains, Alan Rickman believes actors should be careful to maintain their innocence

“I don’t read those things,” Alan Rickman says dismissively when asked about the negative reviews for his new film, Blow Dry. It’s not said in anger, but there is a touch of that languid exasperation which characterises so many of his roles.

He settles back in his chair and agrees that what attracted him initially to the film, a Strictly Ballroom-esque tale of hairdressing competitions set in the northern English town of Keighley, was the prospect of taking on a different, quieter role than those he usually plays. The other attraction was working with Irish director Paddy Breathnach.

“Although I also responded to the script, I was incredibly interested in working with Paddy, because I’d seen I Went Down and loved it,” he says. “Sometimes you see a film and make a mental note that you want to work with that particular director.”

Blow Dry received a pretty unanimous raspberry from the British media on its UK release a few weeks ago. Characterised as a shameless rip-off of other “grim oop north” comic melodramas such as The Full Monty and Brassed Off, the film was criticised for its lack of originality and sloppy script. Does he think the film suffered by comparison with others of its genre?

“Well, genre is a dangerous word, isn’t it?” he says carefully. “When I made An Awfully Big Adventure here in Dublin, it was coming hot on the heels of Four Weddings and a Funeral. Because Mike Newell directed it and Hugh Grant was in it, for some reason people thought – I can’t think why – that they were going to see Four Weddings and a Funeral again, as if Mike Newell would be interested in doing it twice. That’s another film which has acquired its reputation over the years, but at the time people were disaffected by its darkness.”

It’s a fair enough point about an audience’s unrealistic expectations, but An Awfully Big Adventure, with its seedily evocative portrait of a theatre company in dingy, post-war Liverpool, could only be confused with Four Weddings by the wilfully blind or incurably dim. The obvious successors to Four Weddings are Notting Hill and Bridget Jones’s Diary, not just because of the Hugh Grant connection, but for the rather syrupy view of Britain they purvey. But surely these northern working-class films are just the equally sentimentalised flipside of the same coin?

“Well, therein lies the danger,” Rickman sighs. “And I’m sure that it’s a danger here as well, that a country starts to cartoon itself in order to make itself acceptable to the market. I see no reason whatsoever why Britain, or Ireland for that matter, couldn’t have made its own version of American Beauty. But we didn’t.”

Why is that? “I’m not really sure,” Rickman says. “I know that we used to have mature film-makers making mature stories. But it needs a sociologist or a marketing expert to explain these things. What is a northern English comedy? Why does Blow Dry have to be thought of in the same sentence as Brassed Off? What are the forces which come to bear on a story which is actually about the minutiae of small-town life, but which has to be blown up into something everybody understands? Market forces impose certain rules before a film can actually get made.

“I want us to make some more grownup films, and I suppose in a way what it’s about is we’re only just recovering from the effects of 18 to 20 years of cultural torture. Half the time we’re being yanked into the 21st century, while the other half of the country’s trying to stay in the 18th century. It’s difficult to tell your own stories in that situation.”

Some critics have pointed the finger at the influence of Miramax, the US company which, a decade ago, helped to bring the work of directors such as Jim Sheridan and Neil Jordan to US audiences. In those days, the argument goes, companies like Miramax came in at the end of the production process and bought the rights to finished films such as The Crying Game and My Left Foot. Now they’re interfering with the scripts from the very start (Blow Dry, with its superfluous sub-plots and transplanted American teen actors, certainly seems to offer some support to this view). “But you can’t make those generalisations,” Rickman protests. “Miramax was also the company which rescued Dogma, which essentially involved somebody writing a personal cheque to save the film. Miramax also rescued The English Patient, at a point where Anthony Minghella was telling everybody they should just go home. So it depends which way you look at it.”

Dogma, Kevin Smith’s absurdist take on Christian myths from a comic-book perspective, saw a memorable cameo from Rickman as the irascible angel, Metatron. He sees Smith as “part of a Renaissance in America, which is edgy and strong-minded and sexy and smart. Directors like Spike Jonze and Paul Thomas Anderson. I only saw Magnolia recently, and thought it was just brilliant.”

Rickman recently completed filming on the heavily-hyped Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, in which he plays Prof Severus Snape. This portrayal promises to be the latest in a long line of memorable character performances in major blockbusters, including the chief baddie in the original Die Hard. His wonderfully villainous performance as the Sheriff of Nottingham in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves allegedly caused Kevin Costner to commandeer the editing room to cut him down to size.

He seems to have an uncanny knack for making good choices. Last year’s endearing sci-fi spoof, Galaxy Quest, for example, hardly looked all that promising on paper, but has already built up a considerable cult following for its tale of a group of has-been TV stars who save the universe.

“Well, it’s a good, bright, sparky film,” says Rickman. “People were surprised by it, but just ask for a minute: didn’t you ever wonder why some of these people (costars Sigourney Weaver, Tim Allen, Tony Shalhoub and Sam Rockwell) were in it? We all read it and thought it was very original and affectionate. The director, Dean Parisot, was very smart, in that nearly everyone he cast was a theatre actor who could relate to the story. At rehearsal, he just said: “This is about you, this is your story.’ “

Two years ago, he made his own directorial debut, with the low-key but welljudged domestic drama, The Winter Guest, starring Emma Thompson, and he’s currently working on his next directorial project, which he describes as “love story set at the court of Louis XIV”.

“It takes such a big lump out of your life,” he says of film directing. “So you have to know you want to do it. You know you’re going to be pretty much out of action for a year. Then again, it’s a privilege, and it can be a compulsion. In that sense, it’s no different from being an actor. You read something and you want to say those words. As a director, the pictures start jumping off the page at you. But they’re not just pictures; you want to tell that story.

As a director, he says, he still has an awful lot to learn, “but I always knew that I would do it. It was just that I had to get to a point where the job was so strong that I felt I had something to say. It was always about trying to steer it towards something that I believed in. In terms of the visual side of it, that was just me rediscovering my own art school and design background”.

As a producer, he’s currently working with the Irish actor/writer Conor McDermottroe, “who’s written a wonderful screenplay of Eamon Sweeney’s novel, Waiting for the Healer, which Pat O’Connor will direct”. He hopes that film will shoot later this year.

His most memorable role in Ireland up until now, of course, was as Eamon de Valera in Neil Jordan’s Michael Collins. “Thank God, at least I’m not being stoned in the street here for having dared to try,” he says.

He is well aware of the controversy which his characterisation of de Valera provoked. “It’s not so much a question of characterisation, though, as of certain scenes being left out,” he says. “If I were sitting here with the de Valera family, I’d say: `Believe me, I spent a lot of time and energy fighting his corner, in terms of not judging him. But I can’t answer for what the director or the studio do.’ In the script, there was a very important moment – which was cut – which made it clear that he was not involved in the death of Collins. But other forces wanted the film to end on a romantic notion rather than a political one.”

He still thinks the film itself is “a fantastic achievement. What’s the point of whingeing about it? It’s the sort of story that it would need about 12 hours to tell properly, but that isn’t going to happen. The fact that Neil got anywhere with it is miraculous.”

Does he think that, as an English character actor, there is a risk that he will be typecast as the bad guy all the time in Hollywood movies? “I’ve been asked that question before, but I really don’t think it’s true,” he says. “I think if you look at American actors like De Niro, they spend most of their careers exploring the darker side. It’s not my experience of the last 10 years, which is of pouring my energy equally into every job equally. Now when you’ve finished the movie, it either works or doesn’t work, it has a huge publicity budget or no publicity budget. It gets vast distribution or it goes straight to video. But my memory is of six to eight weeks getting involved very deeply in a story and living the character, whether it’s playing Rasputin in St Petersburg one minute or talking to 5,000 Dubliners as Eamon de Valera the next.”

He never, he says, has any idea how successful a film is going to be when he’s working on it. “Some people say to ask the make-up department,” he says. “But on Sense and Sensibility, they were an absolute voice of doom. As an actor, I think that innocence is hugely important to hang on to. You have to hand yourself over to the director.”

And directors? He gives that knowing smile. “Directors are much less innocent.”

Тобто “Версальський роман” він планував ще з 2001 року? О_о